Towards Active Synthetic Data Generation for Finetuning Language Models

Abstract

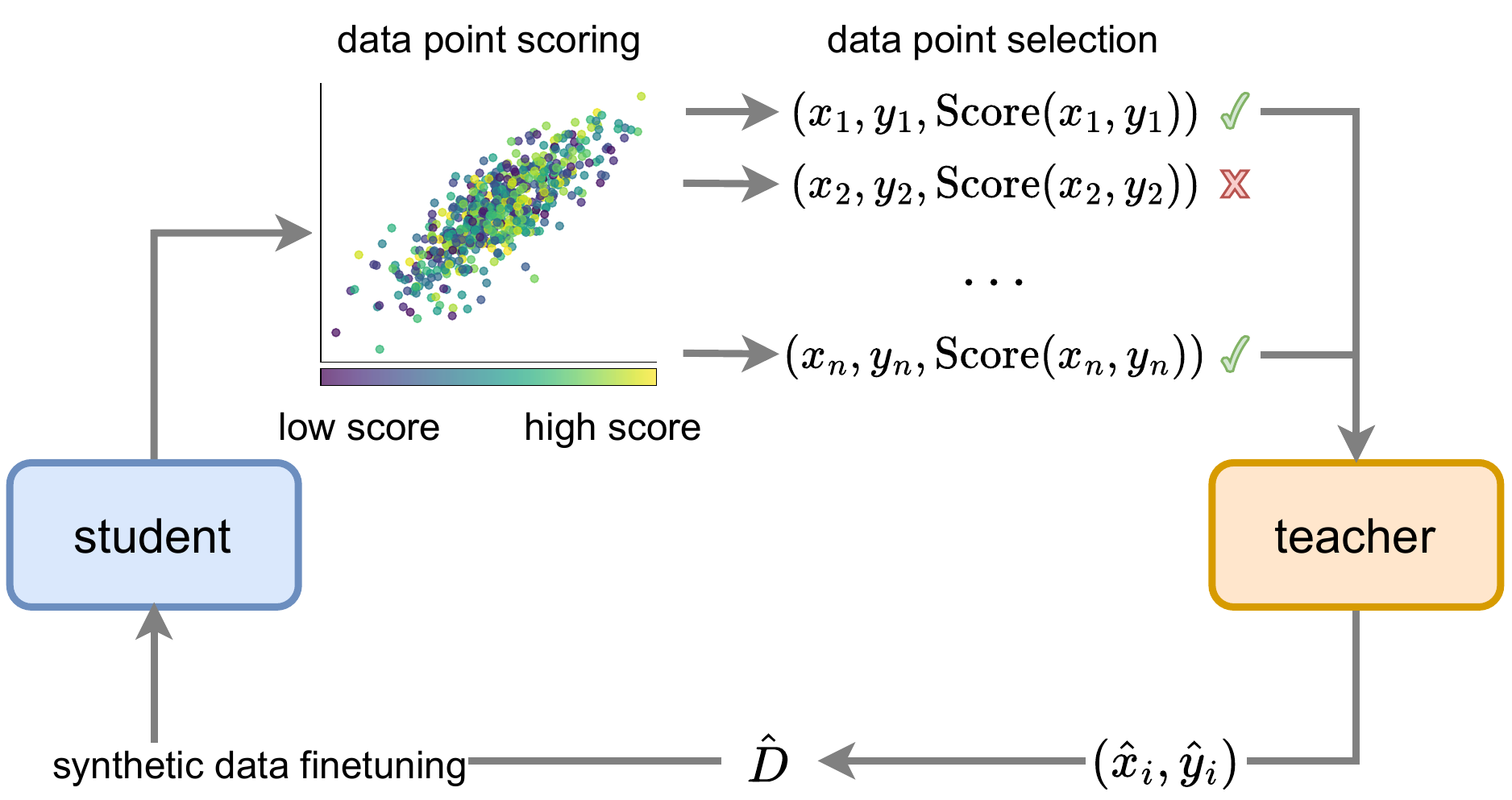

A common and effective means for improving language model capabilities involves finetuning a "student" language model's parameters on generations from a more proficient "teacher" model. Termed "synthetic data", these generations are often produced before any student finetuning, but some work has considered generating new synthetic samples as training progresses. This paper studies and advocates for the latter case, where data are generated in an iterative, closed-loop fashion that is guided by the current state of the student model. For a fixed budget of generated samples, or a budget in terms of compute spent querying a teacher, we show that this curation of finetuning data affords improved student performance over static generation. Further, while there have been several LLM-specific methods proposed that operate in this regime, we find that simple, inexpensive selection criteria from the active learning literature tend to be most performant. We validate these claims across four mathematical and logical reasoning datasets using four different small language models.

On the Fidelity of Synthetic Data to the Original Seed Data

Wait! Synthetic instruction generation is prompt-based: given an example seed question, we ask an LLM teacher to produce a new one. The teacher will simplify, complicate, or inject reasoning and therefore add noise to active learning data scores. So, random selection of a seed instruction for synthetic data generation is optimal?

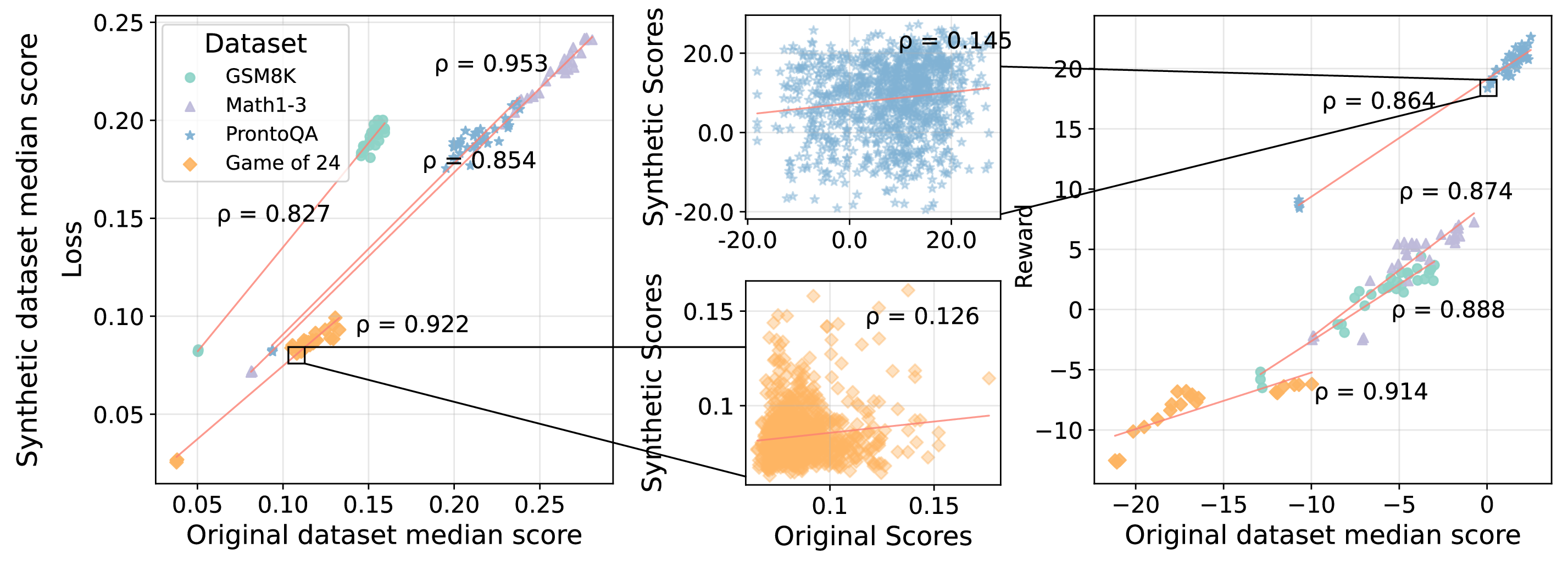

It turns out, that when we score our data before and after iterative synthetic data generation then the scores are similar: showing high rank correlations at the dataset level.

Figure 2: The rank correlations between original and synthetic dataset scores from iterative synthetic data generation. We plot student loss and reward scores and show Spearman's rank correlations (\(\rho\)) between dataset medians before and after synthetic data generation. We zoom in on relationships at an individual data-point level where there is low correlation between the original and synthetic data point scores (centre). The red line is the line of best fit to the data. All rank correlations are highly significant (p < 0.001).

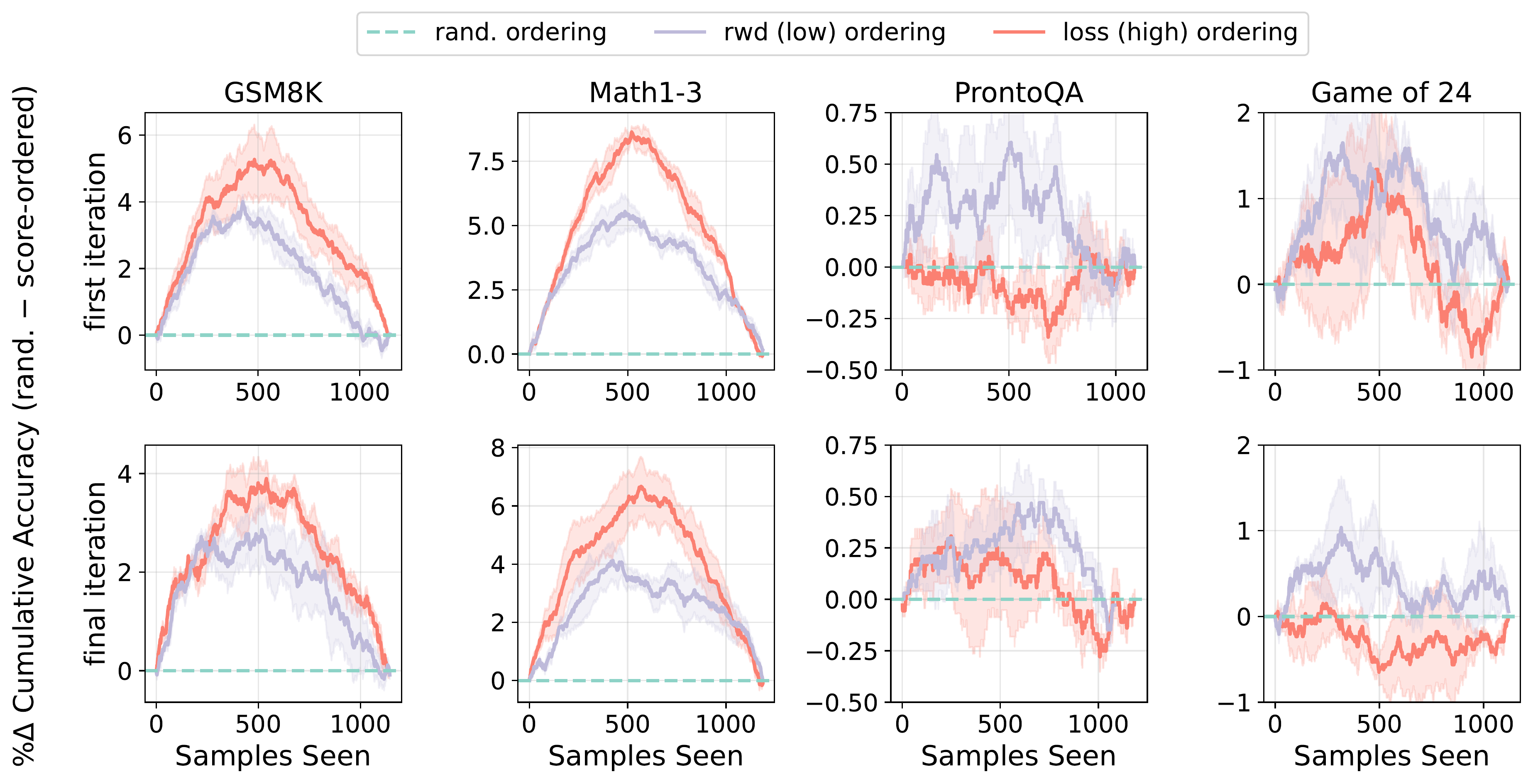

Active learners often select “difficult” data points as they provide a stronger learning signal. For synthetic instruction generation, active selection leads to lower student accuracy on the synthetic data.

Figure 3: The percentage difference in synthetic data cumulative accuracy between samples ordered by score and randomly shuffled. Data are sorted either by uncertainty (high to low) or reward (low to high). Positive values suggest that score ordering picks more difficult synthetic samples in turn yielding lower accuracies. For each original data point we score it using the student model from the first and final iteration of iterative synthetic data generation (rows).

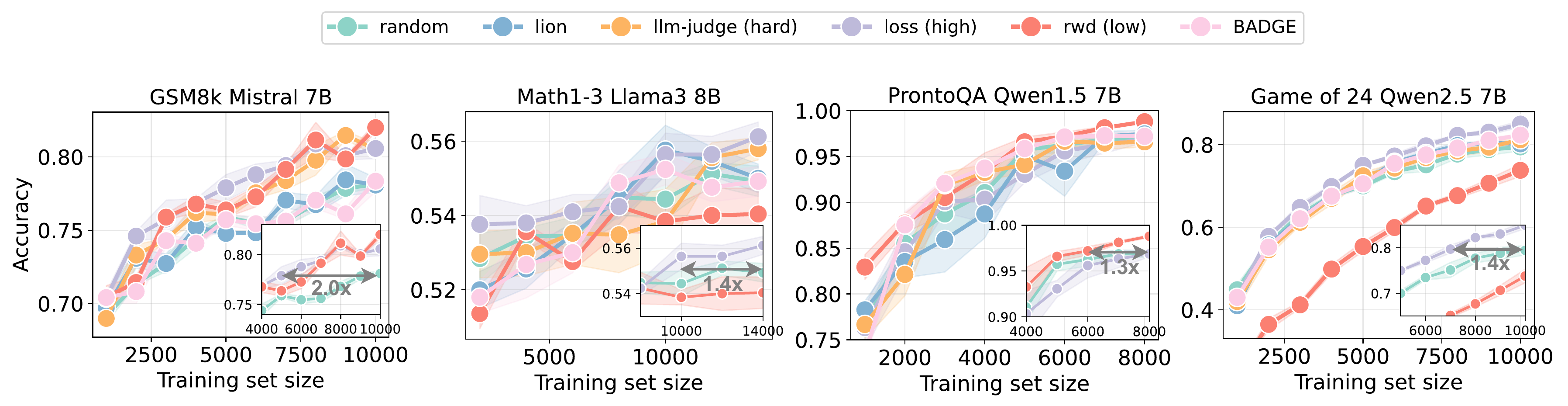

Active Synthetic Data Generation Results

So synthetic data retains qualities from the selected data! The best active methods are 1.3x-2x more efficient than static generation.

Figure 4: Student performance over successive synthetic data iterations with growing training sets. In all cases, selection based on uncertainty (loss) performs approximately as well as LLM-based scoring strategies (rwd and llm-judge), without requiring additional queries to an LLM. Further, for tasks that are out-of-distribution for the scoring model, like Game of 24, these mechanisms can perform even worse than random sampling. Horizontal lines in each inset plot denotes the proportion of data random sampling would require to achieve the same performance as the best active selection strategy in the corresponding experiment.

The best methods? Simplicity wins! Prioritizing high-loss points beats more expensive, complex LLM-as-a-judge methods.

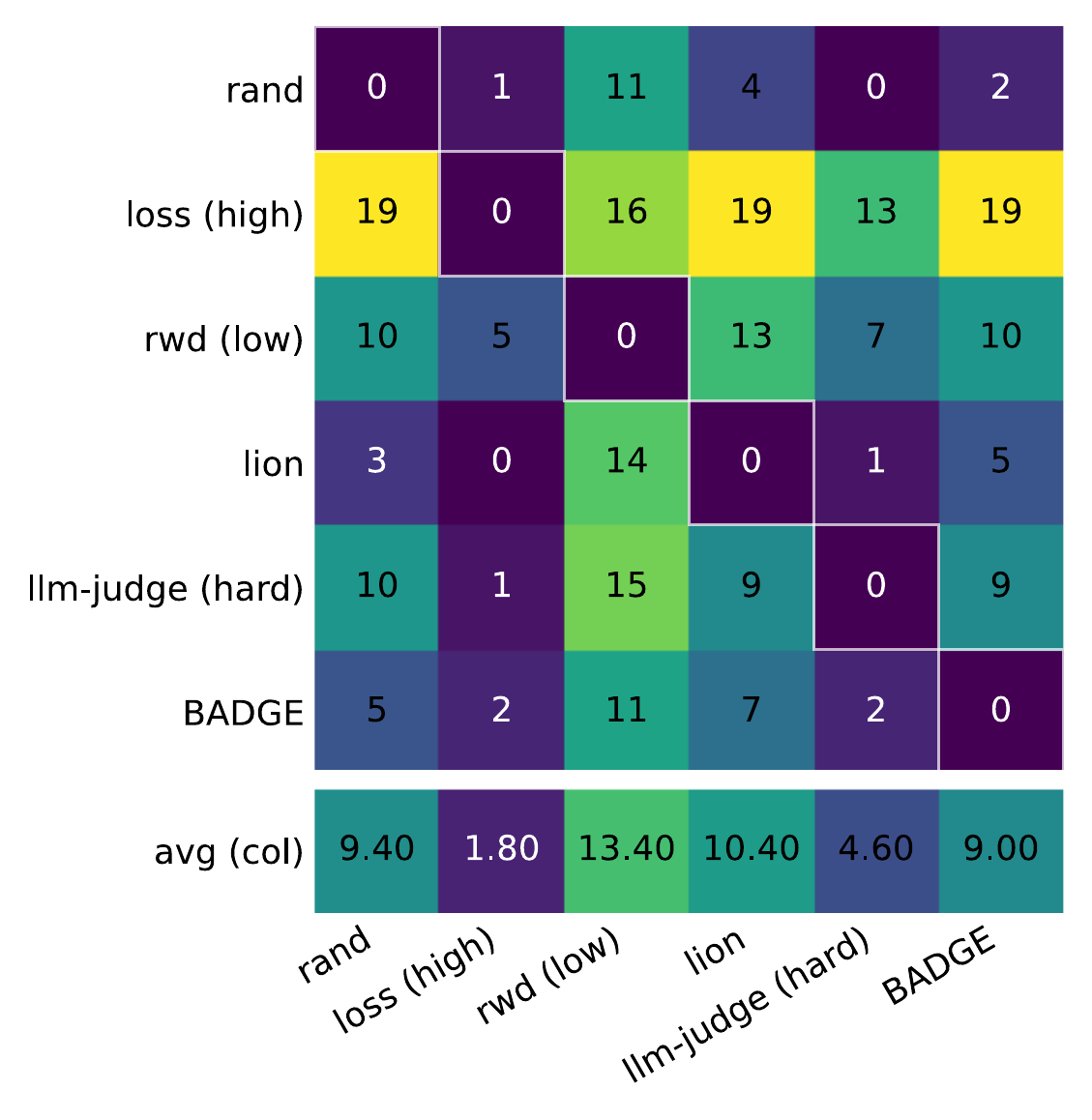

Figure 5: Pairwise winrate over all datasets and methods. \(\mathbf{P}_{ij}\) corresponds to the number of times algorithm \(i\) outperforms \(j\). Overall performance is shown in the last row (lower is better).

Takeaways

- Active selection enables steerable synthetic data generation.

- Active methods are more data efficient than static generation.

- Simpler scoring methods beat complex LLM-based ones.

Citation

@article{kessler2025active,

title={Towards Active Synthetic Data Generation for Finetuning Language Models},

author={Kessler, Samuel and Xia, Menglin and Diaz, Daniel Madrigal and Han, Dongge and Hashemi, Helia and Rajmohan, Saravan and Ruehle, Victor and Ash, Jordan T.},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:2512.00884},

year={2025}

}